Joinery

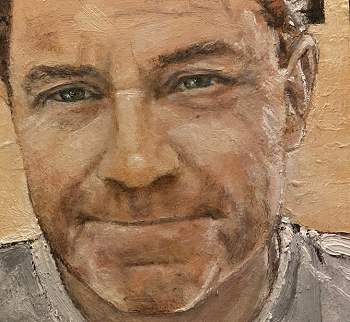

Contributor’s Marginalia: Ted Jean responding to Kelan Nee’s “Translation”

Kelan is a carpenter. He frames his poem with plumb studs and rough rafters, on deep concrete footings in a bank of shifting clouds.

At its core, Kelan Nee’s disorienting “Translation” deals with a sexual encounter, and the ultimately unknowable character of another person, however physically intimate the connection. An unshared language materializes the inadequacy of words to mediate interpersonal differences; hence, the “translation” metaphor. His terse deliberation of that riddle deserves explication and applause. But that’s not my object, here. Instead, I want to advance the idea that a confessed carpenter, by trade, makes poetry that echoes with hammering and the thump of lumber; that his day job colors the tone and attack of his art. To create a poem of such subtlety with crude tools and materials is all the more a marvel.

Poetry is rarely a livelihood. Teacher, mechanic, janitor—most of us write a poem when we get a quiet moment away from the job description. Is it persuasive to suggest that our literary avocation is shaped in important ways by what we do for a paycheck? While I muddled with mixed success in various jobs along the way, my only settled skills are those of a journeyman carpenter. And my poetry is inarguably informed by sweat and callus and the sweet smell of freshly milled fir. I take the liberty of thinking that the craft of Kelan, my fellow tradesman, is similarly influenced. And, as this poem is presumably forthright personal narrative, the congruity of carpenter/protagonist is even more apt.

The structure of “Translation” is deliberate, declarative, percussive, like work done with simple tools. Its short, measured elements are nailed together without artifice or apology. The poem is built. And this is not the delicate finish carpentry of cornice and dentil—it is rough framing, though deadly accurate. Its diction is decided, quotidian. Only three words in the entire poem exceed two syllables. Brief chunks of narrative pronouncement, often two or three to a line, abrupt end stops, a rectilinear joinery of enjambment and caesura accomplish a coarse symmetry, like the fitting of windows and doors into stolid walls:

“We were approached by several street cats.

I knelt: small genuflection. I put out my hand.

She kicked one hard in the side

when it neared her shin. I said, Stop”

By its cadence, we get the impression that Nee is constructing a compelling argument. But the poet’s brusque assertions misdirect; his “home becomes dark. It is small. It clutters / easily.” Kelan tells us in simple, concrete terms precisely what happens in his apparently fortuitous encounter with a French-speaking woman; but neither he, nor we, finally know what to make of it. The authority of his predication and punctuation, the boldness of his brevity, his candid carnality … it all devolves to ambivalence, even outright contradiction:

“… making love

in her bed, she said I could never love you.”

Kelan sketches himself an awkward persona, taciturn, who by words and action is unable to negotiate the subtleties of an enigmatic relationship. As it was for other guys I worked with in the building trades, putting together a lasting bond is beyond his skill set. The romantic coupling is lost in translation, certainly, as suggested by his title; but it is also unfinished business, a house that may never get built.

My premise, though perhaps slim, has legs, I think. In his poem, “The Carpenter,” Jacques Redá argued that the practice of poetry and carpentry are parallel:

“The work I do is not as far away

from his as he perhaps believes: slate

by slate he mends a roof; I build four walls

of writing, word by word, a makeshift place …”

How much more plausible is the linkage when carpenter and poet are one?

“Translation” is classic Nee: clarity of action, narrative concision, ultimate irresolution. His tightly framed structure never gets buttoned up to the wind and rain. Kelan doesn’t offer answers. That’s not his job. Instead, he builds a sturdy, briefly habitable poetic space in which he and we take shelter to ponder the often indecipherable blueprint of life and love.