“Prayer,” Point of View, and in Praise of Empathy

Contributor’s Marginalia: Dick Allen on “Prayer” by Michael Bazzett

In my family history, there’s a story of how, when my great-grandfather Allen was about to be born, someone shouted the news down from the farmhouse to where my great-great grandfather was plowing a lower field.

My great-great grandfather loosed his horses. He abandoned the plow in a furrow.

It stayed there for over thirty years.

With its likewise abandoned farm instrument left in a similar furrow, it’s no wonder that Michael Bazzett’s short “Prayer” immediately caught my attention.

First lines will do that.

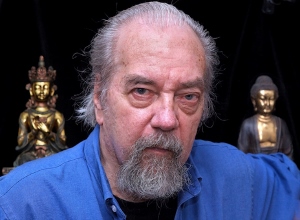

The late John Ciardi, Poetry Editor of the Saturday Review of Literature, famously claimed he read no further than the first line of any submitted poem. Unless it caught him, the poem went into the circular file. Scores of my early poems got thusly dumped.

That was extreme, but still . . . .

My being subjectively caught by “Prayer” wasn’t the deciding factor in this case. The first lines of “Prayer” also welcomed me with the use of the second person point of view. That is, the poem’s first line doesn’t read—in the manner of the narcissistic Confessionalist Poetry lyric—something like, “I drive the old road and I pass a tractor.”

No, this was going to be an empathic poem: “you’ll pass a tractor” (ital. mine). And I was to be reassured by the poet’s use of the first person plural in the third line: “Let us wonder. . . ” rather than, say, “I am wondering.”

It feels strange to bring such attention to a small poem’s point of view. Yet it also feels necessary to do so now. Toward the end of the 21st century’s second decade, contemporary American poetry at last has been loosened from the grip of imitating the first person singular lyric of the Self (i.e. John Berryman, W.D. Snodgrass, Anne Sexton, late Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Sharon Olds, ad infinitum) that was so dominant for over fifty years.

A momentary caution: It’s not enough to be welcomed into a poem by point of view. The great danger of second person and first person plural is how they never stopped being the hallmark of Hallmark cards and worse sentimental and usually rhyming verse. I.e.: “It’s your birthday, so sit in the sun. / We all love you and hope you have fun.”

To avoid such, the best contemporary poems, such as “Prayer,” combine use of a universalizing point of view with that mainstay (thank you, Elizabeth Bishop) of focusing on the concrete specific image.

Bazzett’s specific object is this tractor seen from an old road. “Old road” implies, at least to me, maybe a dirt road in my ancestors’ Vermont. It also sets up a sense of timelessness the poem will incorporate later. The tractor is simply and perfectly described with “nose blunt in the wind” and the additional detail of rust. A human-made piece of technology is united with Nature’s elements.

The poem’s reader, welcomed and invited by “Let us. . . . “ is given further specific details of something animal-like (“hulk”) and bulky (“the engine”). Abruptly, the thing quits, going stone-cold dead.

Somehow, I’ve been made to feel sorry for this abandoned thing, this tractor, left just as lonely here as was my great-great grandfather’s plow.

Bazzett’s third stanza with its ox confirms the mechanical-animal connection. I’m remembering that many humans personify and even give human names to their machines. My father called his running-board Ford “Old Betsy.” I’ve watched a friend weep when her Volkswagen beetle, “Percival,” was being crushed into a junkyard metal square.

Two line stanza poems seem to me like lapping waves, like furrows. With the fourth and final quiet lap we get the prayer and the poem’s title, subject and intent explained. First person plural again: “May we all be blessed.” Not only with the kind of immortality that’s like the near-immortality of an inanimate object, but also with the acceptance that in our faith and demise, Nature will go on. Baby, the rain must fall. After our paltry deaths, the earth/Earth we leave behind us will heal. Let it be so. There’s a kind of Buddhist acceptance here, a comforting we need to be reminded of for all our diminishing days.

Of course that’s nowhere everything that can be said using this lovely and memorable and wise poem. For instance, if we go back over the poem we can also admire Bazzett’s use of the four beats to a line metrical rhythm.

#

Yet, what I also really want to stress—given this chance and this poem and in my small way on behalf of the future of poetry in our century—is the importance of poets and critics remembering how the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes, to have the confidence that it’s possible to speak for and of and with others, is essential for the creation and recognition of significant poetry. When we abandon such confidence and the requirement that our poets spend parts of their lives learning to recognize and communicate their time’s zeitgeist, when we dismiss the age-old Bardic voice, we forget the great genre of Poetry contains more than the subjective first person singular point of view lyric. We diminish our calling. We slight narrative poetry, satirical poetry, persona poetry, didactic poetry, epic poetry, celebratory poetry, dramatic monologues, meditative poetry, even the entire concept of poetry as a fiction-making art. We confine poetry to personal mystery, autobiography, flight and sob.

#

Memorable short lyric poems seem best when they seem spontaneous, no matter how much work has gone into making them appear to have been realized but a moment ago. (The poet, to do so, often works his or her revisions by a quiet process of erasures.)

“Prayer” is what feels like a spontaneous quick observation followed by a naturally occurring heartfelt wish. That it seems so inevitable, so natural, is its gift and blessing—plucked, if you will, from the air.

Given to us. Come to rest in a furrow.